Frames of Reference: A Skateboarder’s View

My essay Explaining Rolling Motion raised some commentary about frames of reference and their equivalence when solving physics problems. I wish to pursue the idea of shifting one’s frame of reference because its use is relatively uncommon in introductory physics courses. Students are asked to solve problems mostly in the (approximately) inertial frame of the Earth at the risk of putting their thinking into a “box”. Notable exceptions are relative motion at constant velocity and the use of the center of mass frame in treating collisions. I believe that more physical situations need to be explored to encourage students to think out of the box. In this essay, I present an early attempt to do just that and what I learned from it. I start with a well-known problem to provide a reference point for what follows. I close with a historical perspective and a few afterthoughts. As can be inferred from the title, part II is contemplated and already in the works.

Table of Contents

The problem (an old standard)

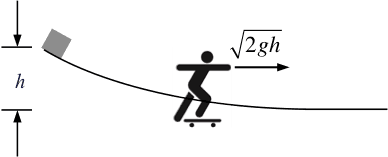

A small block is released from rest at the top of a frictionless non-planar incline. It slides down left to right until it reaches a horizontal surface and coasts to the right thereafter. Neglecting air resistance, find the final speed of the block at the bottom of the incline given the vertical drop h.

Solution

We use mechanical energy conservation between two points, the top and the bottom of the incline. We assume that zero gravitational is at the bottom of the incline.

At the top: ##K_i = 0; U_i = mgh##. At the bottom: ## K_f = \frac{1}{2}mv^2; U_f = 0##.

By conservation of mechanical energy, ##\Delta K +\Delta U=0##. Then,

$$ \left( \frac{1}{2}mv^2-0 \right)+(0-mgh)=0 \rightarrow v=\sqrt{2gh} $$.

The twist

Now consider the reference frame of a skateboarder who is moving to the right with speed ##u= \sqrt{2gh}##. Redo the problem in the skateboarder’s frame of reference to find the block’s initial speed, v0, given the vertical drop h.

We note that at the bottom of the incline the block is at rest in the skateboarder’s (primed) frame and conserve mechanical energy once more.

At the top: ##K’_i = \frac{1}{2}m(-v_0)^2; U’_i = mgh##. At the bottom: ## K’_f = 0; U’_f = 0##.

By conservation of mechanical energy, ##\Delta K’ +\Delta U’=0##. Then,

$$ \left( 0- \frac{1}{2}mv_0^2 \right)+(0-mgh)=0 $$

$$ – \frac{1}{2}mv_0^2 -mgh=0 \rightarrow ??? $$

We have reached the impossibility of having, on the left-hand side, the sum of two negative numbers that must be zero according to the right-hand side. Something is amiss. At this point I ask you, the reader, to please pause, consider your reaction to what you just read, answer the three-choice question below and continue reading if you wish.

How can this situation be resolved?

- Mechanical energy must not conserved in the skateboarder’s frame.

- Mechanical energy is always conserved; there must be an algebraic error in the derivation.

- Mechanical energy is always conserved, this is a trick question.

Note: The original article had a readers’ poll which was removed upon expiration.

The resolution

A savvy skateboarder would realize that mechanical energy (ME) is not conserved in the moving frame. In the lab frame, the normal force is always perpendicular to the block’s displacement and does zero work on the block. In the skateboarder frame, the path of the block is no longer perpendicular to the normal force.

In fact, the skateboarder sees the block’s speed start at some initial non-zero value and then drop to zero and remain zero as if a dissipative force stopped it. Therefore, ME is not conserved in the moving frame and 1 is the correct answer.

Instead of ME conservation, the skateboarder would be well advised to use the work-energy theorem and take into account the work done by the normal force.

OK, but if you were the skateboarder, how would you calculate this work considering the arbitrary curvature of the incline? The answer is by transforming to the lab frame in which the normal force does no work. Let primes denote quantities in the moving frame. Using ##\vec{u}## as the relative velocity between the two frames, we have ##\vec{r}’=\vec{r}-\vec{u}~t##. Then ##d \vec{r}’=d\vec{r}-\vec{u}~dt##. The work done by any force in the primed frame is

$$W’=\int \vec{F} \cdot d \vec{r}’ =\int \vec{F} \cdot (d \vec{r} -\vec{u}~dt)=\int \vec{F} \cdot d \vec{r} -\vec{u} \cdot \int \vec{F}~dt$$

The first term in the right is the work done by the force in the unprimed frame while the second term is ##-\vec{u} \cdot \vec{J} ## where ##\vec{J}## is the frame-independent impulse delivered to the system. Thus, the work done by the normal force in the primed frame is,

$${W’}_N=W_N-\vec{u} \cdot \vec{J}=W_N-m\vec{u} \cdot \Delta \vec{v}’ $$

In this case, ##W_N## is zero. The skateboarder sees the incline move with constant velocity ##-\vec{u}## and, since the block is initially at rest relative to the incline, the skateboarder deduces that ## \vec{u}=v_0 \hat{x}##. Furthermore, according to the skateboarder ##\Delta \vec{v}’=+v_0 \hat{x}## because the block is initially moving to the left with speed ##v_0## and finally comes to rest. Thus,

$${W’}_N=-m (v_0 \hat{x}) \cdot \left( v_0 \hat{x} \right) =-mv_0^2$$

According to the work-energy theorem

$$\Delta (ME’)={W’}_N$$

We already have the left side of the equation from the earlier attempt to solve this in the primed frame. Thus,

$$ – \frac{1}{2}mv_0^2 -mgh=-mv_0^2 $$

From this, it is easy to show that ##v_0=\sqrt{2gh}##.

A second opinion

The skateboarder can sidestep the question of how to account for the work done by the normal force in the primed frame by using combined conservation of mechanical energy and linear momentum. Consider a two-component system with component A of mass ##m_A## being the block and component B with mass ##m_B## the Earth + incline. In this case, mechanical energy is indeed conserved because the work done by the incline on the block is the negative of the work done by the block on the incline while there is no friction to dissipate energy. In the primed frame, both systems are initially moving to the left with speed ##v_0##. When the block reaches the bottom of the incline, it is at rest while Earth + incline are moving to the left with speed ##v’_f##. We have then

$$-m_Av_0-m_Bv_0=0-m_Bv’_f$$

$$m_Agh+\frac{1}{2}(m_A+m_B)v_0^2=\frac {1}{2}m_B{v’}_f^2$$

This is a system of two equations and two unknowns that is solved to give

$$ v_0=\sqrt{ \frac{2gh}{1+m_A/m_B}};~~~v’_f=\sqrt{2(1+m_A/m_B)gh}$$

When ##m_A/m_B <<1##, to a very good approximation, ## v_0 = v’_f = \sqrt{2gh}## which is consistent with the results in the previous section. It should be clear to the reader that in either reference frame momentum and energy conservation gives the exact solution while energy conservation only results in an approximation, albeit a good one.

Historical background and afterthoughts

In my early days of teaching, I had time left at the end of a lecture on mechanical energy conservation. Instead of dismissing the class early, I thought up the skateboarder question on the fly to illustrate that the laws of physics are invariant when viewed from a different inertial frame. I was surprised and embarrassed to discover (with 3 minutes left in the period) that things literally didn’t add up. Feeling the pressure, I dismissed the class promising a resolution next time. In retrospect, asking this question was an act of faith, affirming my belief in the invariance of mechanical energy conservation under the Galilean transformation. Moral: Don’t start something unless you have already established how it will play out.

This experience not only chastised me but also made me wonder whether others shared the same blind spot. I asked undergraduates, graduate students, and colleagues the three-choice question with mixed results. It appears that the belief in mechanical energy conservation is quite robust among students. A few of them sacrificed mathematical rigor on the altar of mechanical energy conservation blithely asserting that ## (-v_0)^2 = -v_0^2 ##. My colleagues’ reactions generally varied from the non-committal “I am busy now, let me take it home with me and I’ll get back to you” to the indignant “Is this a gotcha question?” Only one person was quick to point out the momentum conservation approach.

Some confusion arises partly because the principle of mechanical energy conservation is often formulated improperly in textbooks and on the internet. For example, the current Wikipedia entry states, “The principle of conservation of mechanical energy states that in an isolated system that is only subject to conservative forces the mechanical energy is constant.” A better formulation, which allows the presence of non-conservative forces as long as they do no work, might be “The principle of conservation of mechanical energy states that, in an isolated system on which only conservative forces do work, the mechanical energy is constant.”

I have assiduously avoided labeling the surface contact force as either conservative or non-conservative. On one hand, it could be argued that it is electromagnetic in origin, therefore it can be derived, at least in principle, from a potential. Furthermore, the normal component can be viewed as a conservative spring-like elastic force. On the other hand, if a book is dropped on a table, the book quickly loses its mechanical energy and comes to rest as a result of the same normal force acting on it. So which is it? Conservative or non-conservative? Contact forces are unique in that they necessarily introduce lattice vibrations, that dissipate energy into the lattice. When an object is dropped on a flat surface, there is some ringing which is relatively quickly damped out as all the mechanical energy is dissipated by the lattice vibrations. Similar considerations apply when an object is dragged across the surface. While contact forces are in principle conservative, in practice they unavoidably dissipate mechanical energy by converting some of it into internal energy. Thus, when contact forces are present, the boundary between the work-energy theorem and the first law of thermodynamics becomes blurred.

I am a retired university physics professor. I have done research in biological physics, mostly studying the magnetic and electronic properties at the active sites of biomolecules and their model complexes. I have also dabbled in Physics Education research.

This is a good insight. The key point for me is that we tend to see the universal gravitational field as allowing us to apply the Galilean transformation. If the problem concerned a spring or pendulum the answer would be simpler to see. A pendulum, for example, analysed in a frame where the fixed point is moving.

Another idea would be to consider an observer moving vertically when an object is dropped. Again, it’s clear that mechanical energy cannot be conserved. E.g. The observer could be moving down at the final speed of the object, hence the object ends up with zero KE. In this case, the observer has to calculate the vertical displacement in his reference frame, not in the Earth’s frame.

The key, therefore, is that when the force is vertical and the moving reference frame is horizontal, then the vertical displacement in the two frames is the same.

Another way to look at this problem, therefore, is to say that first in the Earth frame the gravitational force is partially opposed by a normal force, so the nett gravitational force is tangential to the slope. Then, we can resolve this tangential force into horizontal and vertical components. The vertical component is no problem for a reference frame moving horizontally, but the horizontal force is a problem if you try to model it at a horizontal distance-based potential.

[QUOTE="tade, post: 5608483, member: 469644"]kuruman, do you skate? To complement theory with experiment haha[/QUOTE]No, but I admire those who do as long as they don't collide with me (it happened once).

[QUOTE="kuruman, post: 5597491, member: 192687"]kuruman submitted a new PF Insights postFrames of Reference: A Skateboarder's View Continue reading the Original PF Insights Post.[/QUOTE]kuruman, do you skate? To complement theory with experiment haha

Continue reading the Original PF Insights Post.[/QUOTE]kuruman, do you skate? To complement theory with experiment haha

The conclusions I get from this discussion is that although particular reference frames may be used to simplify calculations, 1. there are no incorrect reference frames as such. 2. When adopting a nonstandard reference frame one must be careful not to ignore the reality of the whole physical system (e.g. the Earth) and one must be careful not to blindly apply the computational shortcuts and assumptions conveniently used in the calculations in the standard frame, which no longer apply when attempting to solve the problem in the nonstandard reference frame.

[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5599957, member: 260864"]Sure, if you have a closed system, the Lagrangian must be Galileo invariant, and all 10 conservation laws must hold. However, in this case it's a very complicated … [/QUOTE]Post #10 includes the Newtonian math assuming a closed (isolated) system.

Sure, if you have a closed system, the Lagrangian must be Galileo invariant, and all 10 conservation laws must hold. However, in this case it's a very complicated Lagrangian you can't write down to begin with. That's why we use the effective description with constraints (which are idealized too of course) to simplify the problem. I don't see, what's the problem to understand the calculation concerning the Lagrangian I gave above. I thought it might help to understand the problem, expressed in the article in terms of the Newtonian formulation (which I find much more complicated than the Lagrange formalism).

[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5599941, member: 260864"]Of course the skater's frame is an inertial frame, but that doesn't imply momentum or energy conservation if there are nonconservative forces acting on the block.[/QUOTE]By "momentum conservation" I meant total momentum of the isolated system, not the momentum of the block only, which obviously not conserved.

Why should momentum be conserved? It's not conserved in either frame, because there are forces acting on the block (gravitation from Earth and the constraining forces from the ramp. The latter forces become obviously time dependent in the skater's rest frame, and thus the forces are not conservative in this frame. Of course the skater's frame is an inertial frame, but that doesn't imply momentum or energy conservation if there are nonconservative forces acting on the block.

[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5599641, member: 260864"]The momentum is neither conserved in the restframe of the ramp nor in the skater's restframe[/QUOTE]The skater is an inertial observer. Why wouldn't momentum be conserved in his frame?[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5599641, member: 260864"]in the rf. of the ramp the Lagrangian doesn't depend explicitly on time, and thus that the Hamiltonian in these cordinates is conserved.[/QUOTE]Even if the mass of ramp+Earth was comparable to the block's mass?

[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5599641, member: 260864"]Well, I think the "naive-mechanics explanation" has been very well explained in the article. For me it's very difficult to think in terms of forces, but the action-principle approach makes it immediately clear. It's due to the constaint of the block to the ramp which makes the energy non-conserved in the skater's rest frame, because in this frame the Lagrangian becomes explcitly time dependent. The momentum is neither conserved in the restframe of the ramp nor in the skater's restframe, because in neither frame the independent variable #x# is cyclic (see the posting above, where I corrected some typos). Of course nobody would solve this problem in the skater' frame, since it's immediately clear that in the rf. of the ramp the Lagrangian doesn't depend explicitly on time, and thus that the Hamiltonian in these cordinates is conserved.[/QUOTE]What happens if you include the Earth in the Lagrangian? Would it matter that the calculation was made in the skater's rest frame?

Well, I think the "naive-mechanics explanation" has been very well explained in the article. For me it's very difficult to think in terms of forces, but the action-principle approach makes it immediately clear. It's due to the constaint of the block to the ramp which makes the energy non-conserved in the skater's rest frame, because in this frame the Lagrangian becomes explcitly time dependent. The momentum is neither conserved in the restframe of the ramp nor in the skater's restframe, because in neither frame the independent variable #x# is cyclic (see the posting above, where I corrected some typos). Of course nobody would solve this problem in the skater' frame, since it's immediately clear that in the rf. of the ramp the Lagrangian doesn't depend explicitly on time, and thus that the Hamiltonian in these cordinates is conserved.

[QUOTE="rcgldr, post: 5598821, member: 17595"]Technically, the mass of earth and slide should be included in conservation of mechanical energy in either frame (closed system free from external forces).[/QUOTE]The simple approach in the ramp's frame is not based on the conservation of total energy, just on the work theorem applied to the block: Since the ramp does no work on the block, the block's energy should be constant.However, this assumes that the ramp's frame is inertial, which it actually isn't as the lack of momentum conservation shows. So even if the ramp does no work on the block in the ramp's frame, the inertial force present in that non-inertia frame does a tiny bit of negative work on the block. So the blocks energy is reduced (final KE < intial PE) in the ramp's frame.

The reason that earth's energy can be ignored from a earth based frame, is that that v[sub]0[/sub] = 0, and Δv is very small. The increase in energy of the earth in this frame is1/2 m[sub]earth[/sub] Δv[sup]2[/sup]From a different frame, v[sub]0[/sub] ##ne## 0, and the increase of energy of the earth is1/2 m[sub]earth[/sub] ((v[sub]0[/sub] + Δv)[sup]2[/sup] – v[sub]0[/sub][sup]2[/sup]) = 1/2 m[sub]earth[/sub] (2 v[sub]0[/sub] Δv + Δv[sup]2[/sup])The key difference is the factor m[sub]earth[/sub] v[sub]0[/sub] Δv.For an "exact" solution, the earth needs to be considered as part of a closed system that includes earth, slide, and box (the skateboarder is effectively an outside observer).

Kuruman:I like the approach with momentum of both the Earth and the block, however, since the locus of interaction is also at the surface of the earth (a point of contact via a shaped ramp) it seems that angular momentum comes into the picture.Some of the momentum of the block would indeed be transferred as final linear momentum of the Earth, the Earth would also be imparted angular momentum, since the block end up travelling tangentially to the Earth's surface. Assuming the Earth is rigid, the ratio of the angular to linear momentum transferred involves the moment of inertia of the Earth which of course depends on the density distribution of the Earth. I wonder what is the moment of inertia of the Earth and how much of a role does that play in the answer for v[SUB]0[/SUB]… it may be more complex than what is written in the section "a second opinion"

Can you clarify what you mean by[QUOTE="vanhees71, post: 5599315, member: 260864"]energy is no longer conserved from the skater's point of view[/QUOTE]This seems to imply actual conservation of energy is violated in a particular frame of reference… so I must be missing a subtlety of interpretation.BTW is the energy of the Earth taken into account? There is energy transferred between the two bodies.GENERALLY: Is there any reason we can assume that the Earth can be ignored when using a reference frame other than the inertial reference frame of the Earth and when dealing with an interaction/force involving the Earth?

Great Insight Kuruman!

As usual, the apparent paradox is much easier to understand when analyzed using the action principle. In the original frame we have$$L=frac{m}{2} dot{vec{x}}^2-mgy,$$where ##y## points vertically up. Further we have the holonomous constraint$$y=f(x)$$and thus the action reads$$L=frac{m}{2} [1+f{prime 2}(x)] dot{x}^2-mgy.$$Now it's clear, why seen from the skater's reference frame the energy is not conserved. We have$$x=x'+u t, quad y=y'$$and thus$$L=frac{m}{2} [1+f^{prime 2}(x'+u t)](x'+u)^2-mgy'.$$Since now the Lagrangian is explicitly time dependent, energy is no longer conserved from the skater's point of view.

I agree with rcgldr:You state:"It should be clear to the reader that in either reference frame momentum and energy conservation gives the exact solution while energy conservation only results in an approximation, albeit a good one."What happens if you include the kinetic energy of the Earth in the energy conservation calculations?

Don't forget about the properties of a Tautochrone curve, which is based on a cycloid arc. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tautochrone_curve#.22Virtual_gravity.22_solution

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tautochrone_curve#.22Virtual_gravity.22_solution

Technically, the mass of earth and slide should be included in conservation of mechanical energy in either frame (closed system free from external forces). From a frame where the earth is not initially moving, then vf[sub]earth[/sub] will be slightly below 0 (slightly negative) and vf[sub]box[/sub] will be slightly below ##sqrt{2 g h}##. From the skateboarders frame, v[sub]initial[/sub] will be slightly above (less magnitude) ##-sqrt{2 g h}## and vf[sub]earth[/sub] will be slightly below (more magnitude) ##-sqrt{2 g h}## . The problem is similar to a box sliding down a frictionless wedge on a horizontal frictionless surface, except in this case the mass of the wedge (earth + slide) is huge.

First part, none of the options to vote for are correct. In the second opinion part, from the skateboarders frame of reference, the two velocities of earth and slide v[sub]0[/sub] and vf' are not equal. Assume the velocity of earth and slide increase by Δv (wrt skateboarder). Then the increase in energy = 1/2 Mb ((v[sub]0[/sub] + Δv)[sup]2[/sup] – v[sub]0[/sub][sup]2[/sup]). Since Δv is tiny, then for a reasonable approximation, Δv[sup]2[/sup] ~= 0.The increase in energy ~= Mb v[sub]0[/sub] Δv.

Looking forward to the followup!