What Causes Cancer: Bad Luck or Bad Lifestyles?

What causes cancer? For the most part, cancer is a disease that arises from mutations in the body that accumulate over time. These mutations knock out key tumor suppressor genes involved in repairing DNA or regulating cell division and activate oncogenes that can drive cells to divide uncontrollably and invade other tissues. But where do these cancer-driving mutations come from? Some of these mutations we inherit from our parents, some come about from environmental factors that cause mutations (such as smoking, exposure to UV and other ionizing radiation, or exposure to carcinogenic substances), and some just naturally arise during the process of cell division.

Many cancer researchers are interested in knowing the fraction of cancers that are attributable to each of these sources as this information helps inform what we think about cancer prevention. If most cancer-causing mutations arise naturally during cell division, the so-called “bad luck” theory, then it seems like there is little we can do to prevent these cancers. However, if they arise due to environmental factors, then cancers are due to “bad lifestyles,” and individuals can reduce their cancer risk by adopting healthier lifestyles.

Earlier this year, a paper in Science made a big splash in this field by claiming that about two-thirds of cancers are due to “bad luck” (we previously discussed this study in this Physics Forums thread). Here’s the abstract for the study:

Some tissue types give rise to human cancers millions of times more often than other tissue types. Although this has been recognized for more than a century, it has never been explained. Here, we show that the lifetime risk of cancers of many different types is strongly correlated (0.81) with the total number of divisions of the normal self-renewing cells maintaining that tissue’s homeostasis. These results suggest that only a third of the variation in cancer risk among tissues is attributable to environmental factors or inherited predispositions. The majority is due to “bad luck,” that is, random mutations arising during DNA replication in normal, noncancerous stem cells. This is important not only for understanding the disease but also for designing strategies to limit the mortality it causes.

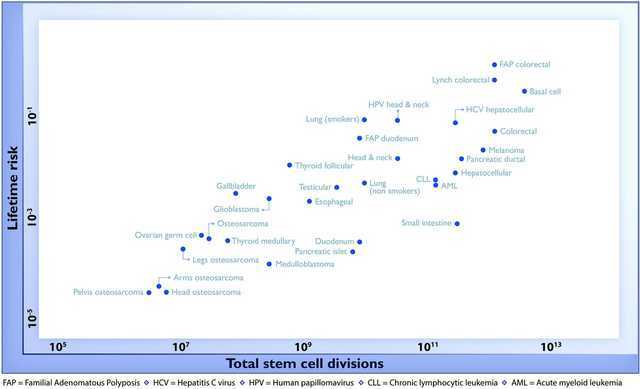

The authors based their argument on the fact that the lifetime risk of developing cancer in a particular tissue varies with the number of cell divisions stem cells from that tissue undergo:

These data make a lot of sense: osteosarcomas (bone cancers, in the bottom left of the diagram) are rare because bone cells divide infrequently, and thus have fewer opportunities to accumulate mutations over one’s lifetime. Other tissues that divide more frequently have a higher chance of accumulating mutations (e.g. as is the case in colorectal cancer at the top right of the diagram). The fact that many of the data points lie near a straight line suggests that the accumulation of mutations during cell division explains most cancer cases (about two thirds of cancer cases, according to the study).

However, not everyone agreed with the conclusions of the study and it drew much criticism from a number of cancer researchers. Now, a new study published this week in Nature challenges the findings of the Science paper, instead claiming that the majority of cancers risk is driven by extrinsic factors (e.g. environmental factors) rather than intrinsic factors (the baseline mutation rate associated with DNA replication):

Recent research has highlighted a strong correlation between tissue-specific cancer risk and the lifetime number of tissue-specific stem-cell divisions. Whether such correlation implies a high unavoidable intrinsic cancer risk has become a key public health debate with the dissemination of the ‘bad luck’ hypothesis. Here we provide evidence that intrinsic risk factors contribute only modestly (less than ~10–30% of lifetime risk) to cancer development. First, we demonstrate that the correlation between stem-cell division and cancer risk does not distinguish between the effects of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. We then show that intrinsic risk is better estimated by the lower bound risk controlling for total stem-cell divisions. Finally, we show that the rates of endogenous mutation accumulation by intrinsic processes are not sufficient to account for the observed cancer risks. Collectively, we conclude that cancer risk is heavily influenced by extrinsic factors. These results are important for strategizing cancer prevention, research, and public health.

The authors base their arguments on numerous lines of evidence:

- Epidemiological evidence. They cite studies showing that cancer incidence varies across geographical locations and over time, which would not be expected if the majority of cancer cases were due to intrinsic factors. Furthermore, they cite studies showing that people who have migrated from areas of low cancer incidence to countries with higher cancer incidence acquire the increased cancer risk associated with their new home.

- Molecular evidence. Different mutational processes show different patterns of nucleotide substitutions in the genome (these different patterns are called different mutational signatures). The authors review various studies of the mutational signatures of various cancers and conclude that the mutational signatures of most cancers are consistent with mutations driven by extrinsic factors rather than intrinsic factors.

- Mathematical modeling. Based on measured intrinsic mutation rates, the authors model what the incidence of cancer should be from a “bad luck”-only scenario and show that it is much lower than the observed cancer incidence rates.

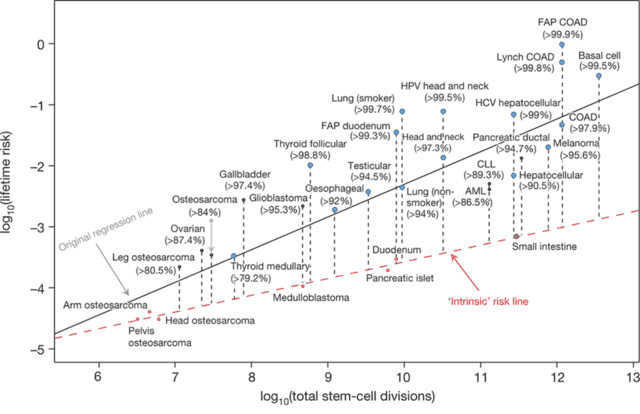

Based on these arguments, the authors re-interpret the scatter-plot from above. They say that the Science paper was unable to see the effect of the extrinsic factors because most of the cancers were affected by the extrinsic factors. Rather, only a small number of cells develop cancer at the intrinsic rate (colored red in the figure below), and the majority of the other cancers have lifetime risks that lie well above the intrinsic risk line:

Overall, this new study is a well-written paper that layers additional nuance and insight onto the initial Science study. The work is important as it suggests that extrinsic factors play a huge role in determining the incidence of cancer, meaning that we should be able to prevent many cancers by limiting our exposure to these extrinsic risk factors. Other epidemiological studies, such as work compiled by Cancer Research UK, have suggested ~40% of cancers are preventable by changes in lifestyle, which is somewhere between the estimates of the Science paper (30%) and the Nature paper (70-90%). However, not all extrinsic risk factors are preventable (e.g. it’s not practical to avoid sunlight) and certainly not are all known. So, the conclusion that 70-90% are due to extrinsic factors likely overestimates the fraction of cancers that are preventable.

Still, the conclusion should encourage doctors and those interested in public health. Most cancers are not unavoidably due to bad luck; rather, many cancers are due to bad lifestyle choices, and these choices are something that is under our control. If you want to reduce your risk of cancer, making changes to your lifestyle—like not smoking, keeping physically active, moderating alcohol intake, and eating at least five portions of fruits and vegetables per day—can reduce your risk of most cancers and, on average, give you fourteen more years of life. This work should stimulate further work to better identify the extrinsic risk factors driving various types of cancers so that more people can learn how to live long, healthy, cancer-free lives.

Further Reading:

Tomasetti & Vogelstein, 2015. Variation in cancer risk among tissues can be explained by the number of stem cell divisions. Science, 347: 78. doi:10.1126/science.1260825

Wu, Powers, Zhu & Hannun, 2015. Substantial contribution of extrinsic risk factors to cancer development. Nature, published online 16 Dec 2015. doi:10.1038/nature16166

Begly, 2015. Most cancers due to ‘bad luck’? Not so fast, says study. Stat News. http://www.statnews.com/2015/12/16/cancers-bad-luck/

Ledford, 2015. Cancer studies clash over mechanisms of malignancy. Nature News. http://www.nature.com/news/cancer-studies-clash-over-mechanisms-of-malignancy-1.19026

Postdoctoral researcher in biophysics.

My areas of expertise include single molecule spectroscopy, structural biology, biochemistry, and evolutionary biology.

I would research the idea of epigenetic changes to DNA – e.g., DNA methylation and histone binding. These are not mutations per se (defined as an addition, change or deletion of one or more nucleotides). But cellular activity which deactivates DNA sequences or changes other characteristics of the sequence. DNA nucleotide sequences are not changed or altered. Just the ability to use them as they were before the change.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epigenetics

This is an addition to the previous post. I apologize for putting this in a separate post, but it has become too late to add an edit to the previous post.

My wife has pointed out to me that the statistics about the number of intrinsic cancer mutations may be underestimated. This is because immune systems destroy some cells with the intrinsic mutations before they might be counted.

Regards,

Buzz

researchers found most cancers – including lung, colorectal, bladder and thyroid cancers – possessed large numbers of mutations that were likely to have been caused by extrinsic (external) factors. Only a few cancers had large proportions of intrinsic (internal) mutations.Hi Issac:

I found the following defining distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic mutations.

The distinction between "spontaneous" and "induced" mutations is based on an operational definition of induced mutations as those which result from intentional exposure of an organism by an investigator to chemicals, radiation or other mutagenic treatment. Spontaneous mutations, then, are those which occur "naturally" in the environment without intervention of an investigator.

I gather from your post that the reason that there are many more extrinsic mutations than intrinsic is that experimenters create so many extrinsic mutations in their laboratories.

Regards,

Buzz

We all know you exponentially increase your risk of getting some cancers by smoking or by having an unhealthy lifestyle. Cancer is caused by a combination of factors – hereditary and environmental factors and the bad luck of random genetic mistakes called mutations that occur when healthy cells divide. While browsing around internet resources like http://www.advancedradiationcenters.com/, etc. I came to that researchers found most cancers – including lung, colorectal, bladder and thyroid cancers – possessed large numbers of mutations that were likely to have been caused by extrinsic (external) factors. Only a few cancers had large proportions of intrinsic (internal) mutations.

[QUOTE=”Ygggdrasil, post: 5364959, member: 124113″]A few examples of modern cancer prevention methods include sunscreen and sun avoidance (from the realization that UV radiation causes skin cancer) and vaccination (to prevent cancer-causing or cancer-promoting diseases like HPV (main cause of cervical cancer) or hepatitis B (increases risk of liver cancer)).

Smoking is a risk factor for heart disease, so the decrease could be primarily due to decreases in smoking. Most sources cite obesity as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease ([URL=’http://www.webmd.com/diet/obesity/obesity-health-risks’]example[/URL]), but you are correct that these are correlations from observational studies that do not show causation.[/QUOTE]

Your right of course but in many ways your examples underline my point, the evidence with UV radiation has been supported in a variety of ways and is informed by a theoretical understanding, what I’m saying is that this isn’t the case with a great deal of lifestyle advice, if only it was. The role of virus infections in cancer is a growing area of interest but most of the research has been focussed on the development of guidelines and treatments based on what we know about infections rather than at the level of the gene. In fact the introduction of a vaccination for HPV is already associated with significant reductions in cases of associated cancers and represents a real advance in cancer control, in contrast most lifestyle advice appears to have little if any impact on health outcomes. Most of the lifestyle advice we are exposed to is around diet and exercise, the evidence related to diet, changes more frequently than the weather (and I live in the UK) and apparently has no effect on the health advice given.

Apparently work looking at the fall in incidence of cardiovascular disease and Alzhiemer’s disease comes from work that controlled for a whole range of known risks and improvements in management, as yet they are unexplained and unexpected, but very interesting.

The idea that negative correlations or anti-correlations don’t falsify causation from the other comment, is of course right, but as you suggest there is no evidence of causation to falsify, most of the correlational work does provide ideas about what variables might be worth investigating further but really shouldn’t inform health advice. The stuff on diet is more embarrassing than useful and reduces the credibility of all health advice, this is worrying in a world in which Doctors now seem willing to lobby for the legal control of lifestyle choices and the introduction of selective taxation.

[QUOTE=”Laroxe, post: 5364816, member: 555853″]Many of the ideas we have are in fact clearly wrong, consider the link of obesity and heart disease which is still promoted and yet the incidence of heart disease has been falling while obesity increases.[/QUOTE]Anticorrelation does not falsify causation. There are so many factors that can lead to those trends, even with a causal connection in the opposite direction.

[QUOTE=”Laroxe, post: 5364816, member: 555853″]I think the there are strong social values associated with “clean” living that impact on the way in which health promotion is studied and presented to people. Generally there haven’t been any major changes (except smoking) in advice since the seven deadly sins (Wrath, Gluttony, Sloth, etc) and in fact little change in the availability in high quality evidence.[/QUOTE]

A few examples of modern cancer prevention methods include sunscreen and sun avoidance (from the realization that UV radiation causes skin cancer) and vaccination (to prevent cancer-causing or cancer-promoting diseases like HPV (main cause of cervical cancer) or hepatitis B (increases risk of liver cancer)).

[QUOTE=”Laroxe, post: 5364816, member: 555853″]Many of the ideas we have are in fact clearly wrong, consider the link of obesity and heart disease which is still promoted and yet the incidence of heart disease has been falling while obesity increases.[/QUOTE]

Smoking is a risk factor for heart disease, so the decrease could be primarily due to decreases in smoking. Most sources cite obesity as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease ([URL=’http://www.webmd.com/diet/obesity/obesity-health-risks’]example[/URL]), but you are correct that these are correlations from observational studies that do not show causation.

I think the there are strong social values associated with “clean” living that impact on the way in which health promotion is studied and presented to people. Generally there haven’t been any major changes (except smoking) in advice since the seven deadly sins (Wrath, Gluttony, Sloth, etc) and in fact little change in the availability in high quality evidence. Many of the ideas we have are in fact clearly wrong, consider the link of obesity and heart disease which is still promoted and yet the incidence of heart disease has been falling while obesity increases. The major risk of death from all causes, and cancer in particular, is age and as average life expectancy increases (and it continues to increase) then the incidence of age related diseases will also increase. The current fall in the incidence of cardiovascular disease and apparently in dementia is unexpected and not well understood but stands as evidence of our poor understanding of what influences these things. Current evidence is usually at the level of “red meat causes cancer” which is both wrong and meaningless. We need specific information that can link an exposure to a specific risk, ideally with a theoretical understanding of how this association works. Virtually everything that happens in our bodies is ultimately under the control of our genes and gene expression is usually under the control something else within the cell or in the cells environment. However generally this has not proven to be a particularly useful level of explanation when it comes to health and disease as it goes beyond what we really understand and can use. Its an area of science, heavily contaminated by politics and medical science is already considered to be among the least reliable subject areas in research, despite its importance.

This is close.

Both lead to it but I would assume lifestyles as there are many factors in our environments that can cause cancer, affecting our genes.

I think this whole discussion may be premature and I see real problems with attributing cause to lifestyle. I base this on a number of issues that may be important in making sense of the arguments. The first would be in the idea that cancer is a discrete disease entity when in reality we are looking at a range of different problems, with different risk factors that result in similar outcomes in the control of cell division. It also seems that cancers really need more changes in the cell in addition to unregulated reproduction, they also need to be able to avoid the systems in place to remove rouge or damaged cells. Childhood cancers as an example, don’t fit well into this debate, inherited risk is not well addressed and in fact will also likely be significant the the sensitivity to certain risks, then the role of viruses an increasing area of interest is ignored.

Then there is the evidence around the risk factors which is usually based on very poor methods, in epidemiology its suggested that if the statistics don’t indicate a relative risk ratio of 2:1 it should be ignored. With smoking this figure is around 20:1 there can be little doubt about its significance but few of the other associations reach the 2:1 level. Studies on diet for example have major problems in data collection often relying on self reports and give results that are highly variable and inconsistent.

There is however evidence that if a persons lifestyle is identified as a cause of health problems this can have a negative effect on the care they receive, both smokers and the obese are often denied access to certain interventions on the basis of increased risk, which is not supported by evidence.

[QUOTE=”Trinity777, post: 5350182, member: 582771″]Thank you Yggg. I appreciate the information. I guess my thought was if we could cause a cell or telomere to regenerate rather than decay, we might find an avenue to reduce the incidence of cancer. Of course the overall anti aging aspect is something I hadn’t really though about, but imagine when combine with all the other factors it would make sense. Thanks again! Trin[/QUOTE]

Unfortunately, longer telomeres and telomere regenteration seem to be associated with an increased risk of cancer. For example, see [URL]https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2014/06/114956/longer-telomeres-linked-risk-brain-cancer[/URL]

[QUOTE=”Ygggdrasil, post: 5349395, member: 124113″]As [USER=547865]@Buzz Bloom[/USER] noted, telomerase is a double-edged sword when it comes from aging. Telomere errosion is one (of many) factors that contributes to aging, so lifespan extension probably requires some means to extend telomeres in senescent cells. At the same time, cancer progression also requires telomere extension, so the worry is that any therapy that extends telomeres would also increase cancer risk.

A large issue, however, is that aging is a multifaceted problem. There are many factors that contribute to aging and if you focus only on one, then the others will kill you instead. Thus, increasing the maximum lifespan of humans requires solving all of the issues simultaneously, a fact made even more difficult because some of the solutions may not be mutually compatible (e.g. the issue of telomere extension potentially promoting cancer). Here’s a link to a nice (though fairly technical) review of the [URL=’http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867413006454′]biological factors influencing aging[/URL]. The article points to nine major factors, of which, telomere errosion is only one: genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication.[/QUOTE]

Thank you Yggg. I appreciate the information. I guess my thought was if we could cause a cell or telomere to regenerate rather than decay, we might find an avenue to reduce the incidence of cancer. Of course the overall anti aging aspect is something I hadn’t really though about, but imagine when combine with all the other factors it would make sense. Thanks again! Trin

[QUOTE=”Trinity777, post: 5347750, member: 582771″]Thanks for the link and I get it about the Telomeres length or being too short have an impact both positive for long, not so great for short. I have been thinking about cell regeneration, possibly Telomere regeneration. Is it possible for regeneration to occur instead of death without disrupting the balance?

A hypothesis might be; regeneration instead of total cell/Telomere death. In that senario the Telomeres would not shorten or when they began the process of shortening a regeneration process would kick in instead. Of course that would mean the “birth” of new Telomeres would not be as abundant, BUT the risk of cancer due to defective and dying Telomeres would then be almost mute? I guess the next step would be to see if we could “encourage” a Telomere to regenerate, finding out what would be the “kick” to initiating that response instead of break down and death. Just thinking out loud.[/QUOTE]

As [USER=547865]@Buzz Bloom[/USER] noted, telomerase is a double-edged sword when it comes from aging. Telomere errosion is one (of many) factors that contributes to aging, so lifespan extension probably requires some means to extend telomeres in senescent cells. At the same time, cancer progression also requires telomere extension, so the worry is that any therapy that extends telomeres would also increase cancer risk.

A large issue, however, is that aging is a multifaceted problem. There are many factors that contribute to aging and if you focus only on one, then the others will kill you instead. Thus, increasing the maximum lifespan of humans requires solving all of the issues simultaneously, a fact made even more difficult because some of the solutions may not be mutually compatible (e.g. the issue of telomere extension potentially promoting cancer). Here’s a link to a nice (though fairly technical) review of the [URL=’http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867413006454′]biological factors influencing aging[/URL]. The article points to nine major factors, of which, telomere errosion is only one: genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication.

[USER=582771]@Trinity777[/USER] , [USER=547865]@Buzz Bloom[/USER]

[QUOTE=”Trinity777, post: 5347750, member: 582771″]Is it possible for regeneration to occur instead of death without disrupting the balance?[/QUOTE]

Hi [USER=582771]@Trinity777[/USER]:

I think you are asking if a medical treatment might someday be invented which would either (1) prevent or slow the reduction of telomere length, or (2) would somehow regenerate telomeres by making them longer. I do not personally know of any such research efforts, and I do not have the knowledge to intelligently try to predict future possibilities. I have a thought about a possibility in a different direction. I think it might be possible to lengthen telomeres in ova and sperm is a safe way. This might provide an infant with a longer life expectancy.

[QUOTE=”Trinity777, post: 5347750, member: 582771″]Of course that would mean the “birth” of new Telomeres would not be as abundant, BUT the risk of cancer due to defective and dying Telomeres would then be almost mute?[/QUOTE]

I have no idea what you mean by “birth of new Telomeres”.

You have apparently misunderstood the relationship between telomere length and cancer. I do not know if this is always the case, but a normal cell commonly becomes actively cancerous when a cell enzyme which is normally inactive lengthens the cell’s telomeres so that the cell can continue to divide abnormally.

Regards,

Buzz

Buzz

Thanks for the link and I get it about the Telomeres length or being too short have an impact both positive for long, not so great for short. I have been thinking about cell regeneration, possibly Telomere regeneration. Is it possible for regeneration to occur instead of death without disrupting the balance?

A hypothesis might be; regeneration instead of total cell/Telomere death. In that senario the Telomeres would not shorten or when they began the process of shortening a regeneration process would kick in instead. Of course that would mean the “birth” of new Telomeres would not be as abundant, BUT the risk of cancer due to defective and dying Telomeres would then be almost mute? I guess the next step would be to see if we could “encourage” a Telomere to regenerate, finding out what would be the “kick” to initiating that response instead of break down and death. Just thinking out loud.

Trin

[QUOTE=”Trinity777, post: 5346757, member: 582771″]So what does that do to my DNA specifically?[/QUOTE]

Hi Trinity:

One idea is that telomeres shorten with age. In some some tissues, this occurs faster than others. If the Biological Age machine measures the length of telomeres of leukocytes, then a correlation of these lengths with age calculated from many samples could be used to make such a assessment.

See

[URL]http://longevity.about.com/od/researchandmedicine/p/telomeres.htm[/URL] .

Regards,

Buzz

I just wanted to say that I liked the article. Great post – [USER=124113]@Ygggdrasil[/USER] !

Hi [USER=124113]@Ygggdrasil[/USER]:

Thank you very much for your clear and useful response to my question.

Regards,

Buzz

[QUOTE=”Buzz Bloom, post: 5321246, member: 547865″]A very interesting article. I am wondering if this kind of study might show whether the length of telemeres might play a role. Telemeres shorten with each cell division, and when they are too short, the cell can no longer divide.[/QUOTE]

The studies focus mainly on the mechanisms that create cancer-causing mutations in cells, but they do not address how these cancer-causing mutations lead to disease. A lot of work over the last few decades has gone into figuring out what specific mutations lead to cancer (for a good review see [URL=’http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867400816839′]Hanahan and Weinberg, 2000[/URL] and [URL=’http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867411001279′]Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011[/URL]), and activation of telomerase is certainly important for carcinogenesis. Nearly all malignant cancer cells are able to extend their telomeres in order to allow unlimited cell division, and this process has been described as an essential hallmark of cancer cells.

Hi [USER=124113]@Ygggdrasil[/USER]:

A very interesting article. I am wondering if this kind of study might show whether the length of telemeres might play a role. Telemeres shorten with each cell division, and when they are too short, the cell can no longer divide.

Regards,

Buzz

I liked the article too. I wondered if there would be any correlation between lower "Biological Age" and those with a reduced risk of Cancer. Specifically, can the lifestyle of one with a lower Biological Age change how DNA ages and responds?As a point of reference for myself, my Biological Age testing hooked up to a machine, came back at 18 years younger than what I am. So what does that do to my DNA specifically? Trinity777

Nice article, thanks for writing it. I still have an open mind about the basic question. The debate highlights the difference between retrospective studies which attempt to test a given hypothesis with available historical data and truly prospective studies which test a given hypothesis by using the hypothesis to make definite testable predictions regarding the outcome of a carefully controlled future study.Apportioning importance of different causal factors is always a challenge in science when the systems are complex and many factors are in play.